Testing the Black Box (1/2): A Practical Approach for Evaluating Bio FMs

The implementation of Biological Foundation Models (Bio FMs) in biopharma represents a massive, multi-dimensional investment that extends far beyond simple capital expenditure. It can be a strategic commitment involving infrastructure, change management, and the recruitment of rare cross-disciplinary talent. To justify these stakes, organizations must use rigorous benchmarking frameworks to determine which models offer the best operational fit. By integrating biological and clinical data into unified numerical embeddings, these models are becoming a sophisticated framework for next-generation clinical decision-support.

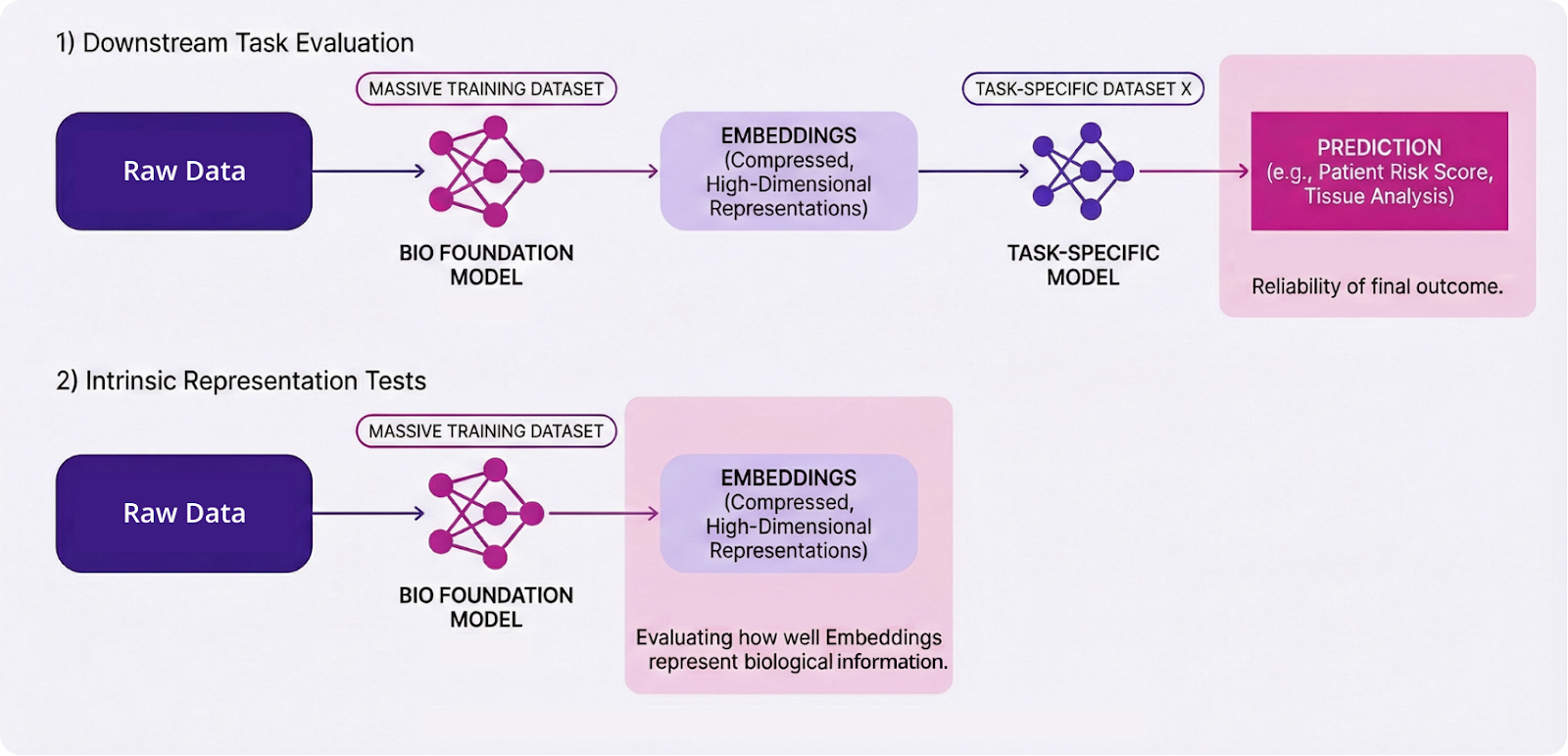

Bio FMs serve as backbone models, trained on high-fidelity, real-world data—including whole slide images (WSIs), multi-omics, and clinical records—allowing them to unify vastly different modalities into a single representation. This generalist model can then be plugged into a specialist downstream model, to perform a task with significantly lower data requirements. This embedding-centric approach can provide a multi-dimensional view of patient information that powers downstream models to reveal deeper, actionable insights.

Consequently, the central question for biopharma leaders is shifting from “Do we need a foundation model?” to “How do we know this particular model is good enough to help us make decisions?”

The answer can only be found through evaluation. Unlike large language models (LLMs), which can be at least stress‑tested on standardized exams or coding challenges, Bio FMs operate in a domain with noisy ground truth, heterogeneous data types, and no universal benchmark. Even current evaluation frameworks are notoriously difficult to implement and generalize; they are subject to constant academic criticism and rapid iteration. In the case of multi-modal Bio FMs, these challenges are compounded by questions of how data modalities perform individually versus what specific insights are gained through their fusion.

The same Bio FM can perform differently depending on which tasks, metrics, and datasets are used to evaluate it. Evaluated one way, it may appear state‑of‑the‑art. Evaluated another way, it may offer no advantage over a simple linear baseline.

Ultimately, the goal is simple: to distinguish models that merely look sophisticated from those that are reliable engines for discovery, development, and other clinical decisions.

The Challenges of Evaluating Foundation Models

While Bio FMs offer a transformative approach to representing life across various scales, their transition from experimental tools to reliable clinical assets faces significant hurdles. Here we explore a few of the key evaluation challenges:

1. The Interpretability Issue

Bio FMs often function as black boxes, meaning their internal decision-making logic is opaque and difficult for humans to decipher. This lack of transparency creates a fundamental gap in scientific understanding; even when a model produces an accurate result, researchers may not fully understand the biological mechanisms or features the model used to reach that conclusion. Without interpretability, it can be difficult to validate the model's logic against established biological principles.

2. The Data Leakage Issue

One very common type of data leakage occurs when information from the pre-training dataset leaks into the test dataset. As Bio FMs are trained on massive amounts of data, including publicly available datasets, it is important to ensure the new data used in downstream testing has not already been used and internalized during the model’s initial unsupervised training phase. It is important to ensure that the Bio FM is learning (generalizing) rather than just memorizing by keeping the training data and test data separate. However, in biology, it is extremely easy to have dependency across data points. Most obviously due to the way that data is reused in research and testing: one sample can provide 100s of data points whose entanglement is easy to lose track of... but also through more complex paths (up to and including evolutionary pathways)

3. Misalignment with Real-World Workflows

Evaluation practices may rely on narrow, static, and unimodal snapshot tests that fail to reflect the dynamic nature of clinical and biological decision-making process. While a model may excel at a discrete task—such as classifying a histopathology image—real-world workflows are inherently longitudinal and multi-staged. Therefore, it is essential that they are designed for integration into existing clinical workflows, ensuring they augment decision-making without introducing operational friction or disrupting the high-pressure environments of biopharma and the drug development process.

4. Structural and Data Limitations

While biological information is vast, most of it remains trapped in unstructured formats or siloed across institutions, leading to a significant scarcity of "ground truth" paired datasets where diverse readouts—such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and spatial imaging—are measured from the same biological sample. This makes it difficult for models to learn the precise cross-modal correlations required for clinical-grade performance. This is compounded by the multi-scale complexity of biology. To truly understand the dynamics of health and disease, models require paired data that spans these scales; however, such cross-scale datasets are rare and technically difficult to produce.

.png)

5. The Trust Gap for High-Stakes Deployment

Creating trust in Bio FMs therefore requires more than impressive performance numbers; it demands rigor, reproducibility, and clear evidence of biological relevance. Trust grows when models are evaluated on external, realistic datasets, when results are comparable across methods, and when limitations are made explicit. Evaluations must reflect the nature of biology: they must be inherently multi-scale and multi-modal, capturing the complex relations between molecules, cells, tissues, organs, and patients. Without such validation, FMs will excel in artificial, constrained settings and yet fail when confronted with the messy data of real experiments, patients, and clinical workflows.

One way to achieve this is by moving beyond accuracy measurements to include explicit uncertainty quantification, distinguishing between aleatoric uncertainty (the inherent stochastic noise in biological data) and epistemic uncertainty (due to lack of data & gaps in knowledge).

How are Bio FMs Evaluated

Because of the wide range of potential applications for Bio FMs, evaluation should be conducted through several complementary approaches. This requires breaking down the overarching goal of "biological utility" into measurable sub-components:

- Functional Utility: Does the model improve performance on discrete downstream tasks?

- Operational Robustness: Does the model generalise to out-of-distribution (OOD) data and novel biological contexts?

- Representational Integrity: Does the model capture biologically meaningful hierarchies within their embeddings?

While these technical evaluations are essential, they are ultimately proxies designed to answer one central question: Do the model's predictions hold up against experimental and clinical reality? The role of Bio FMs as general-purpose backbones means that no single metric can fully capture their utility; a rigorous assessment must combine downstream task benchmarks with intrinsic representation tests.

1. Functional Performance: Discrete Task Assessment

Evaluation must first determine whether a Bio FM actually improves performance over existing methods on discrete tasks. This functional assessment typically occurs at two levels: supervised performance (the model’s precision in executing a specific, labeled task) and generalization (the ability of a model to apply learned biological logic to entirely new, unseen data).

- Evaluation of Downstream Tasks: At this level, the Bio FM’s embeddings are used as features (i.e. inputs for a downstream model) or the model is fine-tuned on specific endpoints like patient stratification, prognosis, or drug potency (e.g., IC50 prediction). Performance is commonly quantified with standard metrics like AUROC or AUPRC. However, because Bio FMs integrate disparate modalities, they often enable "de novo" tasks—such as predicting proteomic shifts from histopathology images—that were previously impossible to attempt. Here, high scores here may be misleading; for example, if data leakage allows the model to memorize the training distribution, or if systemic dataset biases and batch effects lead the model to latch onto spurious correlations rather than learning the underlying biophysical rules.

- Robustness and Generalization: To distinguish biological reasoning from pattern matching, "stress tests" should also be conducted:

- Out-of-Distribution (OOD) Robustness: Tests if a model remains reliable across distribution shifts, such as data from different clinical sites, varying sequencing platforms, or divergent patient cohorts.

- Zero-Shot Extensibility: Evaluates the model’s ability to predict on entirely new biological tasks without additional fine-tuning. The name "zero-shot" refers to the number of labeled examples (shots) required to train the model before it can perform a specific task. In a "zero-shot" regime, you give the model zero examples of the specific task you want it to perform. You are testing its ability to generalize its vast "pre-trained" knowledge to a new problem without any extra training.

Recent benchmarks indicate that Bio FMs may struggle to outperform specialized linear baselines in strict zero-shot regimes, highlighting the difficulty of true generalization. For translational applications, OOD stability is critical; a model that fails in OOD settings lacks the performance needed for high-stakes clinical contexts.

2. Intrinsic Evaluation of the Backbone Embeddings

Intrinsic evaluation focuses on the quality of the Bio FM’s latent representations (embeddings) before task‑specific fine‑tuning. The goal is to determine if the model has captured a rich, biologically meaningful organization of data. In practice, this involves probing whether embeddings recover known biological structures—such as cell-type clustering, disease subtype separation, or the reflection of regulatory networks—without modeling unwanted batch effects.

Frameworks used interrogate the model’s internal representations through varying degrees of abstraction and intervention include:

- Linear Probing: This involves training a shallow linear classifier on top of frozen embeddings (where internal knowledge is locked and unchangeable) to determine if specific biological features—such as protein function, cell type, or disease state—are explicitly and linearly separable within the model's internal representation.

- Topological and Neighborhood Analysis: This method analyzes the intrinsic geometry of the latent space to verify if the model’s internal map preserves biological hierarchies, such as evolutionary lineages, regulatory network motifs, or disease progression trajectories.

- Interventional and Causal Probing: This advanced approach "stresses" the model by introducing digital mutations or in silico knockouts to observe how the embedding shifts, thereby validating whether the model has captured underlying causal biophysical rules rather than just statistical correlations.

Conclusion

To maximize the value of Bio FMs as biopharma assets, organisations must implement a multi-level evaluation framework that explicitly accounts for the unique constraints of biological data. Rather than relying on a single metric, this framework must operate at multiple layers: intrinsic evaluation of the Bio FM embeddings to ensure representational integrity, as well as functional assessment of the downstream model to measure practical utility, generalization, and robustness. Integrating uncertainty quantification to separate stochastic noise from lack of information can also help bridge the trust gap, ensuring the model has captured fundamental biophysical rules rather than spurious correlations. Ultimately, the translational utility of a Bio FM is contingent upon its cross-modal representational alignment and its ability to maintain hierarchical fidelity across discrete biological scales, serving as a high-dimensional, invariant backbone for predictive modeling.