Why Biopharma Needs Its Own AI: Bio FMs vs LLMs

Summary

Biology foundation models (Bio FMs) are a newer class of AI that learn directly from experimental data—sequences, structures, images and multi‑omics—rather than from text. Unlike Large Language Models (LLMs) that have been trained on text to capture the essence of our language, BioFMs work on native "data of life" to capture the essence of biology. By integrating information across scales (from genes to tissues to clinical outcomes), they can serve as a new tool for clinical biomarker and drug development leads, to optimize processes such as biomarker validation, patient stratification, or patient enrichment, improving the overall likelihood that a therapy will reach the market.

Artificial intelligence has been recently propelled forward by foundation models (FMs). The most well-known category, LLMs, are typically transformer-based models that compress huge amounts of text into dense numerical representations, known as embeddings, and from it learn to perform many human cognitive functions such as reasoning, planning, and synthesis. Impressively, top LLMs have shown to score around 83–90% on conceptual biology exams.

However, when it comes to biopharma-related tasks, typically performed by clinical biomarker or drug development leads, LLMs face limitations. This is because the decision-making process is based on available biological data - and biology is a dynamic system, where molecules, cells, and tissues are in continuous states of evolution. Not only can they not be fully represented by text, but biological systems interact across scales and formats—sequences, structures, images, and multi-omics— that together encode the language of life.

Performing tasks based on such diverse data requires Bio FMs, which can learn directly from this experimental data. Instead of predicting the next word, they learn the latent patterns of proteins, DNA/RNA, histology, and other modalities. This article introduces FMs, contrasts Bio FMs with LLMs, and illustrates their critical potential in drug development and precision medicine.

2. Defining the Different Types of Foundation Models

What Is a Foundation Model?

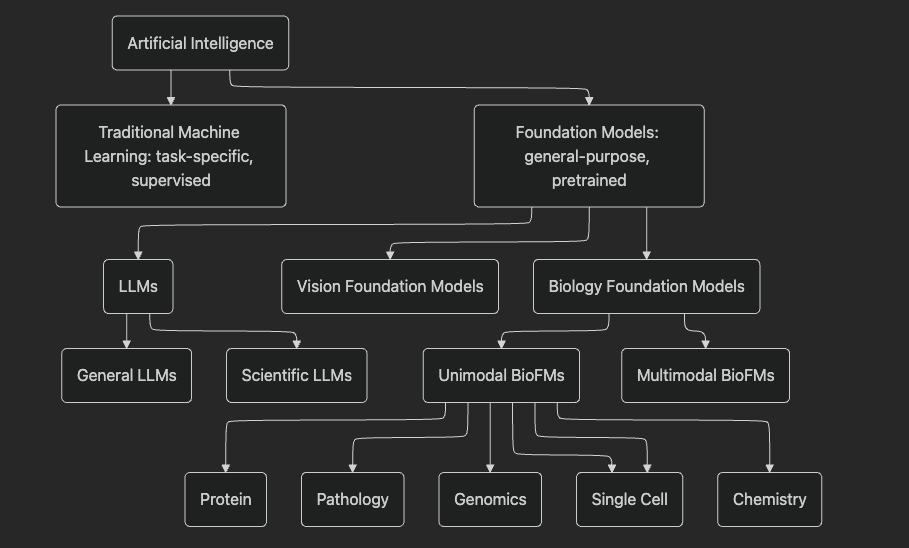

Before comparing foundation models and LLMs, it is important to understand how foundation models differ from traditional machine learning (ML) models (figure 1).

A traditional ML model is a narrow, task-specific system that learns to map inputs (e.g., a biopsy image) to outcomes (e.g., a diagnosis) based on a collection of labeled examples. Among many ML models, today the most common architecture is the neural network. The development life cycle of traditional ML often assumes the model to be trained from scratch for each problem or task. This way the ML models can be viewed as ``specialists.”

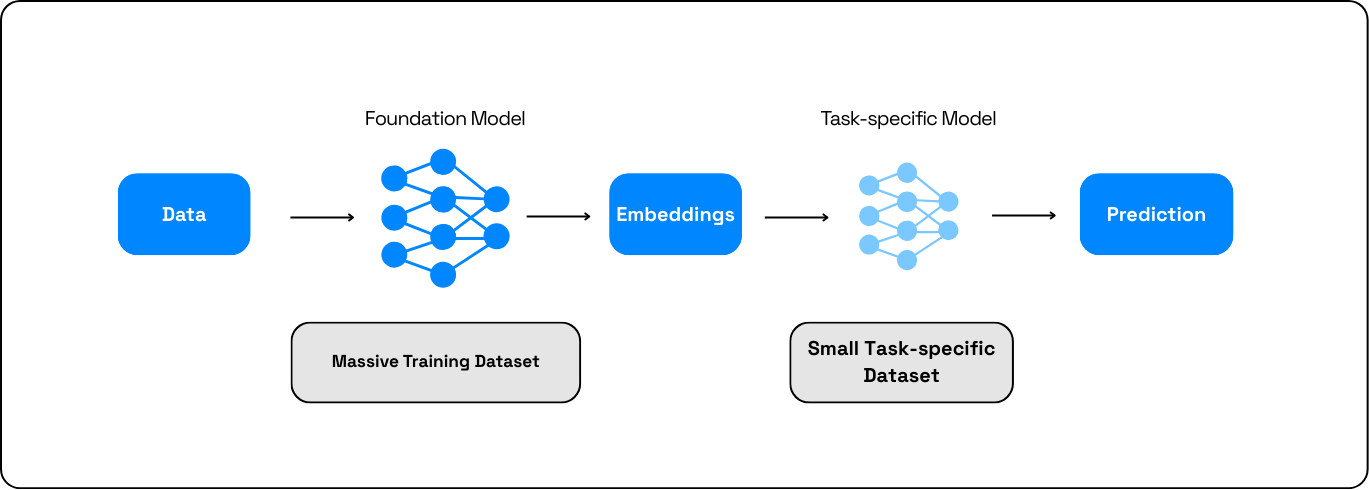

FMs, in contrast, are “generalists.” They are typically built around an architecture known as the transformer, which is a complex large neural network with up to trillions of parameters. Based on massive pretraining data, the FMs can build general representations and understanding of various phenomena such as human biology. This understanding transcends individual tasks, allows them to leverage more data in any given task, and ultimately achieve better task performance than when using a ML model alone. The development life cycle also can kick off with a warm start whereby the training of the general pre-trained model is continued on an often smaller dataset relevant to a downstream task. This process is known as fine-tuning.

Depending on the application, sometimes the traditional ML and FM models can be joined to work together. First, the FM generates unified representations, called embeddings, which then serve as inputs for downstream ML models for specialized task performance. In this combined approach, foundation models function as universal backbones—text, vision, or biological—designed to support many downstream tasks with minimal additional training. Thus, FMs do not replace traditional ML entirely, but rather subsume and extend their capabilities by providing a powerful shared representation layer that the ML then maps to the output.

A foundation model's overall performance and ability to generalize is fundamentally determined by combining massive and diverse datasets with an architecture and training objective that encourages the extraction of general, reusable knowledge.

Large Language Models: General and Scientific

LLMs first entered biomedicine when general‑purpose models were applied “as‑is” or lightly adapted to biomedical text. Researchers realised that the same transformers that powered web search and chat could answer medical questions, summarise clinical notes, and mine PubMed at near‑human performance. This early phase was mostly about using internet‑trained LLMs on biomedical corpora, sometimes with modest fine‑tuning, to support tasks like question answering, literature review and basic clinical decision support.

As their impact grew, the field moved towards building scientific LLMs. These models kept the same transformer backbone but were pre‑trained or heavily fine‑tuned on scientific literature, clinical notes, and other types of biological data that can be represented as text. They shifted the centre of gravity from general web text to domain‑curated data, enabling richer reasoning over molecular biology, cell states and drug properties. Scientific LLMs are now tailored for tasks such as genomic variant effect prediction, gene regulatory element discovery, single‑cell perturbation forecasting and data‑driven molecule design.

However, even scientific LLMs are still language models: they reason over text-like data of biology, not the raw experimental measurements themselves. This creates several persistent challenges that only true foundation models of biology can overcome:

- They remain language models that cannot directly understand biological measurements in formats that are different from text.

- They remain constrained by reporting bias and gaps in the literature, limiting fidelity for under‑studied diseases, cell types or populations.

- They cannot capture multi‑scale interactions across DNA, RNA, proteins, cells, tissues and patients, because much of that signal never appears in text.

To address these challenges, Biology foundation models are trained directly on sequences, structures, images and other formats.

Unimodal & Multimodal Bio FMs

Unimodal and multimodal foundation models differ in what data they see and therefore in how much of biology they can capture.

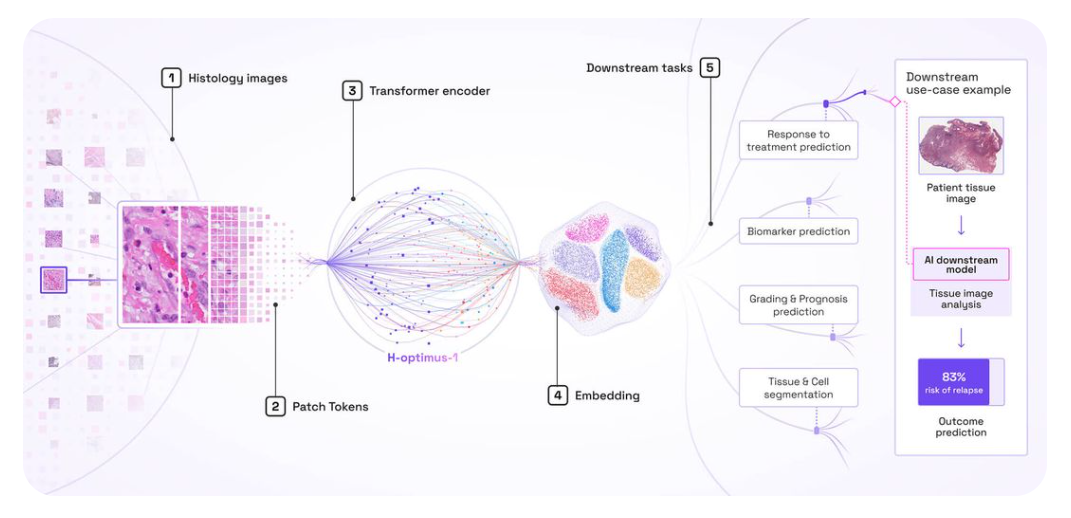

Unimodal foundation models (unimodal FMs) are trained on a single data modality. In molecular and cellular biology, this might be only scRNA‑seq, only DNA sequence, or protein sequences. Depending on the modality, they can be trained to perform a defined set of tasks. For example, protein language models learn from millions of protein sequences and predict structure or functional motifs. Vision‑based models, like those trained on large histology image collections, produce embeddings to perform tasks such as diagnosis (figure 3). Unimodal FMs already capture richer structure than task‑specific models because they see broad, large‑scale datasets within that modality. Although these models excel within their modality, they cannot model relationships across data types.

Multimodal foundation models (MFMs) emerged in the early 2020s, as researchers extended transformer‑based foundation models beyond language to handle multiple data types in a single model. In mainstream AI, early multimodal FMs appeared in computer vision–language systems, which jointly learned from images and text. Their goal was to move away from siloed, task‑specific networks and instead learn a shared latent space that could understand and generate across modalities, for example, matching images to captions or composing new images from text prompts.

In biology and medicine, the same idea appeared, driven by two converging trends. First, high‑throughput technologies such as next‑generation sequencing, single‑cell RNA‑seq, spatial and epigenomic assays, proteomics, and advanced imaging created a flood of heterogeneous data. Second, large‑scale consortia like the Human Cell Atlas, HuBMAP and HTAN generated multi‑omic readouts on millions of cells, sometimes measuring two or three modalities in the same cell. Traditional pipelines treated each modality separately, with different models for genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, or imaging, making it difficult to understand how changes at one layer affect other layers and propagate through the system.

MFMs were developed to solve this fragmentation problem. They are pretrained on diverse omics and measurement types, and can learn a unified representation that spans multiple modalities such as genes, transcripts, proteins, cell states and even clinical context. This allows a single model to support many downstream tasks by learning from massive amounts of data, e.g. characterizing tissue and cell‑state heterogeneity, inferring gene function, integrating batches and modalities, and predicting responses to perturbations or drugs.

In short, multimodal foundation models arose as it became clear that biology is inherently multiscale and multimodal, and that unlocking its structure required models that natively integrate these layers, rather than stitching together isolated, unimodal analyses.

3. Comparing Bio FMs and LLMs

Large language models (LLMs) and biology foundation models (Bio FMs) belong to the same family of FMs, but they play very different roles in the life sciences. Understanding how they overlap and where they diverge is key to seeing why biomedicine now needs models that “speak” biology, not just language.

Both LLMs and Bio FMs are large transformer-based neural networks trained in a self‑supervised way on massive datasets. Rather than learning one narrow task at a time, they learn rich internal representations that can be reused across many downstream problems. They can capture long‑range dependencies and complex relationships: between tokens in a sentence for LLMs, or between genes, cell states and molecular readouts for Bio FMs. In that sense, they share the same architectural DNA and the same “pretrain once, reuse everywhere” philosophy.

From there, however, their paths diverge. LLMs are trained on text (and, for multimodal LLMs, on text plus images, audio and video). Their core objective is to predict the next token in a sequence. That simple goal forces them to internalise patterns in language and, indirectly, much of what is written about biology and medicine. Bio FMs, by contrast, are trained directly on experimental measurements: DNA and RNA sequences, chromatin marks, protein structures, histology images, single‑cell and bulk omics, sometimes coupled with clinical trajectories. Unimodal Bio FMs focus on a single layer, such as scRNA‑seq; multimodal FMs align several layers into a shared latent space that spans genes, proteins, cells, tissues and patients.

Because of this, the advantages of each class of model are complementary. LLMs excel at knowledge synthesis and interactions with humans. They can read and summarise vast literature, draft protocols, assist with coding and documentation, and act as conversational agents for clinicians and scientists. They are ideal whenever the problem is “in the world of words”: question‑answering, guideline interpretation, educational support, or reasoning over reports and notes.

Bio FMs, on the other hand, offer biological fidelity and multiscale integration. By training on the “data of life” rather than on its textual description, they can detect subtle regulatory motifs, variant effects, pathway structures and cell‑state transitions that may never have been written down. Multimodal Bio FMs can connect genomic variants to expression changes, to protein networks, to tissue architecture, to clinical outcomes, enabling digital twins and in silico perturbations that are grounded in real measurements rather than inferred from the literature.

These strengths come with distinct challenges. LLMs struggle with hallucinations, inherited biases, privacy risks, interpretability, and out‑of‑distribution behaviour, especially in high‑stakes clinical settings. Even when fine‑tuned on biomedical text, they remain constrained by what has been published and by the limitations of tokenisation and long‑context reasoning. Bio FMs inherit many of these issues and add their own: they require large, carefully curated and aligned multi‑omic datasets, enormous compute budgets, and rigorous, biology‑aware benchmarks. They raise difficult questions about patient data governance, representativeness across populations, and how to validate model‑driven hypotheses experimentally.

Seen together, LLMs and Bio FMs are not competitors but collaborators: one model class reads and reasons over what humanity has written about biology; the other learns directly from how biology actually behaves. The future of AI in biomedicine lies in orchestrating both.

4. Examples of Foundation Models in Drug Development

The promise of biological FMs is evident in early applications to cancer and pharmacology:

Compound screening and repurposing – FMs that can rapidly screen millions of compounds to identify those most likely to target specific cancer‑related proteins. By analysing vast drug–target interaction data, they uncover repurposing opportunities, identifying existing drugs with unexpected efficacy against certain cancer types or molecular targets.

Personalised treatment prediction – By integrating genomic data with drug–target interactions, FMs predict patient‑specific drug responses and suggest personalised treatment strategies.

Variant effect and RNA splicing models – There are RNA FMs built to predict the effects of pathogenic noncoding variants, how steric‑blocking oligonucleotides modulate splicing and model tissue‑specific gene expression. Its ability to design splice‑modulating oligos highlights how FMs can directly drive therapeutic development.

Histology‑based biomarkers – Vision FMs that learn from hundreds of thousands of histology images. The embeddings they generate improve diagnosis, prognosis and treatment‑response prediction, enabling the development of accurate biomarkers from small cohorts.

Multimodal patient models – Multimodal FMs that aim to combine omics, imaging and clinical trajectories to create digital twins of patients. These models can answer counterfactual questions (e.g., “What if we administer this drug earlier?”), optimize trial designs and prioritise promising interventions.

5. Conclusion

The rise of Large Language Models (LLMs) has transformed AI, yet their focus on text data limits their ability to model the description of life. Foundation Models (FMs) of Biology overcome this by learning directly from experimental data—sequences, images, and multi-omics—providing crucial biological fidelity. Unimodal FMs excel at single tasks, while Multimodal FMs integrate diverse data types, enabling multi-scale integration and virtual experiments like in silico clinical trials. LLMs remain valuable interfaces, but Bio FMs offer the computational engine for discovery, accelerating drug development and precision medicine.

References

- Cui, H., Tejada-Lapuerta, A., Brbić, M. et al. Towards multimodal foundation models in molecular cell biology. Nature 640, 623–633 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08710-y

- Bhattacharya, Manojit et al., Large language model to multimodal large language model: A journey to shape the biological macromolecules to biological sciences and Medicine Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids, Volume 35, Issue 3, 102255

- Wei, J., Yang, Y., Wang, X., et al. A Survey of Scientific Large Language Models: From Data Foundations to Agent Frontiers (2025).

- Chengqi Xu, Olivier Elemento; The potential and pitfalls of large language models in molecular biosciences. Biochem (Lond) 27 May 2024; 46 (2): 13–17.

- Gong, X., Holmes, J., Li, Y., et al. Evaluating the Potential of Leading Large Language Models in Reasoning Biology Questions (arXiv:2311.07582v1, 2025).